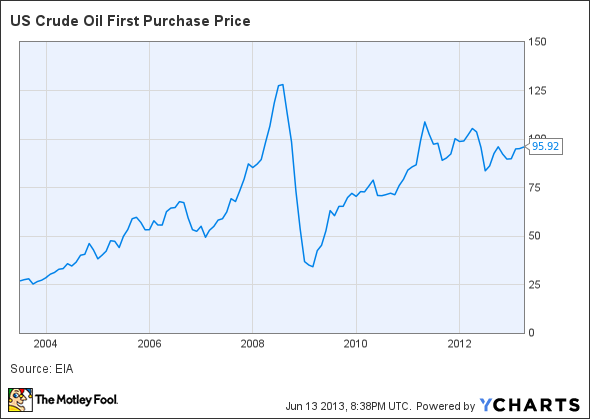

A quick look at a 10-year oil price chart reveals a clear trend: Oil prices are going up. Moreover, oil price increases are not a mere artifact of normal inflation. While the U.S. consumer price index has increased just 26.4% over the past 10 years, oil prices have gained a whopping 257%!

Oil Prices vs. Inflation, data by YCharts

The pace of price increases has been anything but steady, but if you exclude oil’s rapid spike from mid-2007 to mid-2008 and the subsequent crash period from mid-2008 to mid-2009, you can see a clear uptrend.

US Crude Oil Price Chart, data by YCharts

Given this clear uptrend in oil prices, the conventional wisdom today is that oil prices are headed higher, both in real terms and in nominal terms. In fact, when my colleague Travis Hoium recently wrote that U.S. gas prices would never hit $5, dozens of people spoke out to disagree. Many said that they expect gas prices to rise well beyond $5 by the end of the decade.

However, this conventional wisdom is probably wrong. First, rising oil prices have significantly reduced long-term demand for oil, as users have implemented efficiency improvements and substituted cheaper fuels (including renewable energy and natural gas) when possible. Second, high oil prices have stimulated the development of new drilling technologies and a new round of crude oil discoveries. In fact, the International Energy Agency stated last month that the recent “positive crude and product ‘supply shock’ could prove as transformative for the oil industry as was the rise of Chinese demand during the last 15 years.”

In short, the market has worked just as it should: The change in oil prices changed the behavior of consumers and producers. We now live in a world where there is ample excess oil supply — the IEA recently estimated OPEC’s “effective spare capacity” at more than 3.7 million barrels per day — and supply will grow at least as quickly as demand for the foreseeable future. As a result, oil prices are likely to stagnate; in fact, expressed in real terms, oil prices are more likely to fall than to rise going forward.

A new environment

Not too long ago, many oil market-watchers were concerned about “peak oil”: the idea that oil production was nearing a peak, after which declines at existing oil fields would outpace any new production. An article in the January 2012 issue of Nature magazine argued that oil had passed a “tipping point” where increases in demand could no longer be met by supply increases. The authors posited a global production “ceiling” of approximately 75 million barrels per day, beyond which increases in demand would lead to rapid price inflation because of the lack of additional supply.

The Nature article appears to be well researched, but it was ultimately untimely. While the authors concluded that oil supply — and, to a lesser extent, oil demand — had become inelastic, it now appears that the problem was just one of timing.

New extraction techniques such as hydraulic fracturing can be unprofitable when oil prices are below $80 (although that breakeven cost seems to be dropping), but the potential supply of oil grows significantly once prices rise beyond that level. However, the effect is not immediate; it takes time to develop new wells and build the necessary takeaway infrastructure, particularly pipelines. While oil prices spiked well above $80 in 2008, they remained above that level for less than a year. Oil prices have only remained consistently above this $80 “tipping point” since 2011.

Similarly, efficiency technologies such as hybrid car engines are more expensive than conventional internal-combustion engines. When oil prices spike, consumers don’t all immediately run out to replace their gas-guzzling cars with more fuel-efficient models. However, over time, sustained high oil prices do change car-buying behavior, driving market-share gains for small cars, hybrids, and turbocharged engines.