The virus is thought to be carried by fruit bats, which don’t show any symptoms, and it is believed these are the main natural vector for the virus into humans.

From a scientific perspective, the virus inhibits type I and II interferon (IFN) signaling. The processes that ensue are beyond the scope of this report, but to simplify, this inhibition results in the concurrent inhibition of something called phospho-STAT1 nuclear import. When a macromolecule or big molecule (say, RNA, for example) needs to enter the nucleus of a cell, it binds to a protein called an importin, so called because they help import material into the nucleus. Importins are a kind of tag that signals to grant permission into the nucleus in a cell. If the macromolecule has an importin attached, it gets through to the nucleus. If it doesn’t, it doesn’t. The Ebola virus stops the tagging, and in turn, stops the importation.

This causes the commonly associated symptoms – vomiting, diarrhea, headache, confusion etc. – and eventually, in many patients, death.

The Latest Outbreak

The 2013 ZEBOV outbreak was far deadlier, relatively speaking, than many people realize. Before this outbreak, the most cases associated with a specific outbreak was 318, with 280 deaths. This means the 2013-16 outbreak was 100 times bigger than any other in history going back to the 1976 first-identification. It started in Guinea, as mentioned, and within a week or so of first identification had spread to Liberia. It subsequently spread to Guinea, Sierra Leone, Nigeria, Spain, the US, the UK, France and Germany over a period of about ten months.

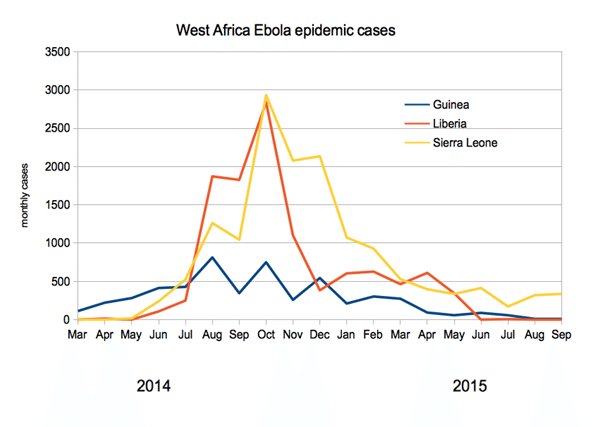

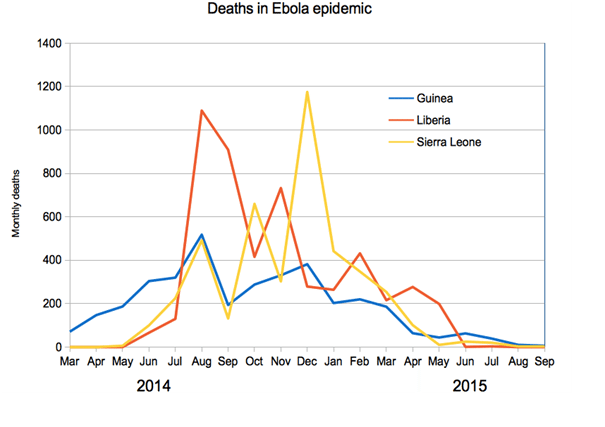

The outbreak officially ended in January 2016, when on January 14 the WHO declared West Africa Ebola-free. However, isolated cases remain, and many are still recovering from infection. At outbreak end, the WHO reported 28,657 cases and 11,325 deaths. The vast majority of these cases (28,611) occurred in Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea, coming in at 10,675, 14,122 and 3,814 respectively.

The chart below shows the number of monthly cases in the three most severely affected regions:

The next chart shows the number of monthly deaths in each of the three affected regions across the period generally regarded as active:

Trial Design

Before we get into the individual vaccines, it’s worth sidetracking for a brief discussion of trial design and approval requirements. In a standard drug approval process, a company would pitch its drug against various predefined endpoints and conduct the trial based on these endpoints. Because of the decline in Ebola infections over the last six months however, there aren’t going to be enough infected individuals to conduct a trial to the scale that an agency like the FDA would generally require. Plus, there is something a tad disturbing about giving an Ebola patient a placebo in the midst of hemmorhagic fever if any trial were to be placebo-controlled. As such, a number of alternate methods are going to be required. There are two primary methods through which an Ebola vaccine developer can demonstrate to global health authorities that its candidate is effective.

Image 3 source

Image 3 source