Fracking is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it provides natural gas, a domestic energy source that is blissfully unscathed by volatility in unstable regions, and that has a lower carbon footprint than coal. On the other hand, fracking presents several risks that are as yet unresolved, among them, the potential for groundwater contamination and increased seismicity, and the looming problem of something called fugitive methane emissions.

Fracking, methane, and climate change

Let’s talk about that last one. In terms of global-warming threats, methane makes carbon look like a mewling kitten, at least on a per-unit basis. While we emit far more carbon dioxide than methane, methane packs a much more potent wallop once it’s out in the atmosphere.

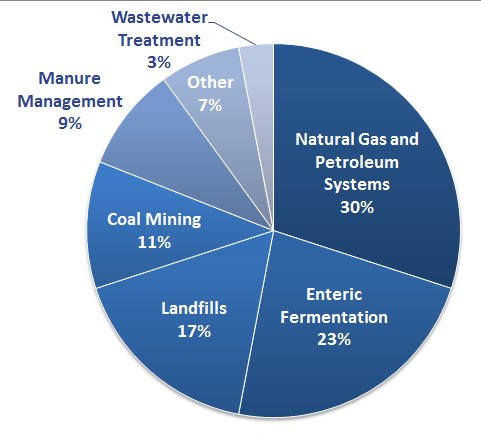

In the case of natural gas extraction and transportation, enough methane leaks along the way that some people have argued that it cancels out whatever carbon savings we might realize by switching away from coal. Further still, natural gas and petroleum systems are the U.S.’ biggest contributors to methane emissions. This could all pose a problem to the natural gas industry if ever our society gets serious about reining in its contribution to climate change.

Methane Emissions by Source

Source: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

Fortunately, some companies are demonstrating the prescience and initiative to get out in front of this issue. They have partnered with environmental NGOs and academic researchers to conduct robust scientific studies of the fugitive methane problem, seeking to identify its scope and its origins.

Anadarko Petroleum Corporation (NYSE:APC), EnCana Corporation (USA) (NYSE:ECA), Pioneer Natural Resources (NYSE:PXD), Southwestern Energy Company (NYSE:SWN), and Talisman Energy Inc. (USA) (NYSE:TLM) funded and participated in a comprehensive research initiative organized by the Environmental Defense Fund, involving more than 90 partners — universities, scientists, research facilities, and oil and gas companies. The study’s results were published yesterday. It was the first in what will be a series of studies analyzing methane leakages along the natural gas supply chain. This first study focused strictly on the extraction phase.

The broad conclusion is that EPA estimates of methane emissions from natural gas extraction sites are largely accurate, meaning that the rules the agency promulgates are founded on accurate assumptions. However, a more granular reading of the study leads to some interesting takeaways, namely that some areas of extraction have far less of an impact than EPA thought, and others have far more.

The researchers found that well completions in the study group generated lower methane emissions than the EPA had estimated, probably because companies have been successful in their use of a control method known as a “green completion.” Meanwhile, emissions are higher than EPA estimates for valve controllers, also called pneumatics, meaning that equipment leaks are an area where fracking companies have an opportunity to reduce methane emissions further.